Barracoon

In the fall of 1913 Booker T. Washington did something he didn't get to do very often -- he took a real vacation. With a group of friends he spent two weeks in a small Alabama town called Coden on Mobile Bay. He wrote home enthusiastically about getting up at five in the morning and catching fifty fish using an old fashioned pole and line with a hook at the end. "The new fangled fishing apparatus I have never had any use for or success with," he wrote home to his wife, Margaret.

Ironically, one of the landmarks near Coden, a sight mentioned by Washington in one of his last speeches, was the wrecked remains of Clotilda, the ship that in 1860 had illicitly brought captured Africans to America to be sold as slaves. The shipowners' attempt to scuttle the ship and thus hide evidence of this crime was only partially successful, and Clotilda's hull, sticking out of the water at low tide, became a local landmark.

in 1927, a young Zora Neale Hurston, an anthropology student at Barnard College, traveled to Alabama (supported by a grant from Carter Woodson's Association for the Study of Negro Life and History and with matching funds from the American Folkore Society). She interviewed Cudjo (or Kossolo as tells her he was called in Africa) Lewis, the last survivor of the Clotilda's crossing from Africa and a resident of the Africatown community established by him and fellow ship mates after Emancipation.

Only now, over eighty years after it was written, is Hurston's account of those interviews being published. The book's title -- "Barracoun" -- comes from the the Spanish-derived word for an enclosure where black slaves were kept before being herded onto ships. Hurston's book transcribes extensive conversations she had with Cudjo and which she wrote down in dialect just as they were spoken. At that time these transcribed conversations were deemed too hard to read or, perhaps, too "black" for publication. As Tayari Jones writes in a review of the book for the Washington Post, "Hurston’s fidelity to Kossula’s voice may have kept Barracoon from being published almost 90 years ago [when] Viking Press wanted 'the Life of Kossula, but in language rather than dialect.' Hurston, who died in 1960, refused such revision, and her manuscript eventually ended up in the Howard University library archives."

The newly published "Barracoun" is a powerful document, both for the way it communicates so much about the experience of Cudjo including his vivid memories of and longing for his African home even 75 years after he had left it, and for what it reveals about Hurston, best known as the author of the novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, published in 1937. She was a sensitive listener and a determined practitioner of the then relatively new field of cultural anthropology which she was studying with famed Columbia University professor Franz Boas. Cudjo tells Hurston -- and through her us -- about experiences we know happened but which we don't often hear described by those who went through them. "De boat we on called de Clotilde. Cudjo suffer so in dat ship. Oh Lor'! I so skeered on de sea. De water, you understand me, it makee so much noise. It growl lak de thousand beastes in de bush. De wind got so much voice on de water...."

Cudjo tells Hurston about his early days as a slave. "De work very hard for us to do 'cause we ain' used to workee lak dat. But we doan griev' bout dat. We cry 'cause we slave. In night time we cry, we say we born and raised to be free people and now we slave. We doan know why we be bring 'way from our country to work lak dis. It strange to us. Everybody lokee at us strange. We want to talk wed de udder colored folkses but day doan know what we say. Some makee fun at us....De American colored folks, you unnerstand me, dey say we savage and den dey laugh at us and doan come say nothin' to us..."

After hearing in 1865 that a war has been fought and that they are now free, Cudjo and others of the men and women from Clotilda think first of returning to Africa. "We work hard and try save our money," says Cudjo. "But it too much money we need. So we think we stay here." As Hurston's narrative unfolds, Cudjo and the others resign themselves to staying in Alabama. They find work in saw mills and powder mills and for the railroad. They plant gardens, raise vegetables and "put de basket on de head and go in de Mobile and sell de vegetable, we makee de basket and de women sell dem too." Evenutally they are able to buy land. They call their settlement there "Africatown."

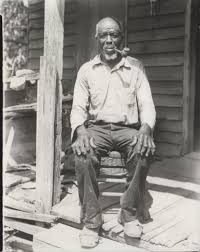

Cudjo marries, fathers five sons and a daughter who dies at the age of 15. "Her mama," says Cudjo, "take it so hard. I try tellee her not to cry, but I cry too." Hurston records that when Cudjo tells her of the death of another of his children, his son David killed in a fight, "there was a muted mournful pause, in which I could do nothing but wait with my eyes in the China-berry tree lest I appear indecently intrusive. Finally he came back to me...." When Hurston photographs Cudjo he asks to do it at the Old Landmark Baptist Church, in the cemetery where his wife and some of his children rest.

When, finally, Hurston leaves to go back to New York, she records that she and "Kossula, who is called Cudjo" had become "warm friends" and "it was a very sad morning in October when I said the final goodbye and looked back the last time at the lonely figure that stood on the edge of the cliff that fronts the highway...He wanted to see the last of me. He had saved two peaches, the last he had found on his tree, for me."

Zora Neale Hurston's rare combination of personal warmth, spiritual depth, intellectual curiosity and gift for expression is on display in "Barracoun." Five years after her sojourn near Mobile Bay talking to Cudjo Lewis, this unusual combination of talents and accomplishments attracted the attention of the Rosenwald Fund and I'll write about that in my next post. It did not work out well. Stay tuned!